Photographer Cory Richards shares his most intimate struggles – against post-traumatic stress, alcoholism, infidelity – and how he found a way to move forward.

Photographs by Cory Richards.

After surviving a level 4 avalanche, the adventurer Cory Richards’ first thought was to capture this moment in a photograph. This “selfie” ended up on the cover of National Geographic.

On April 8, explorer and photographer Cory Richards embarked on his third expedition to climb Everest.

As Richards recounts, he entered the world of high-risk adventure as a troubled teenager to confront his demons. However, these demons haunted him and over the years manifested as alcoholism, infidelity, and trauma after a brush with death.

Richards, now 35, states that he is ready to climb Everest and has made peace with his past through “a unique solution: honesty.” He has shared the story of his life with audiences worldwide, illustrating it with some of his most famous photographs. Here are some excerpts.

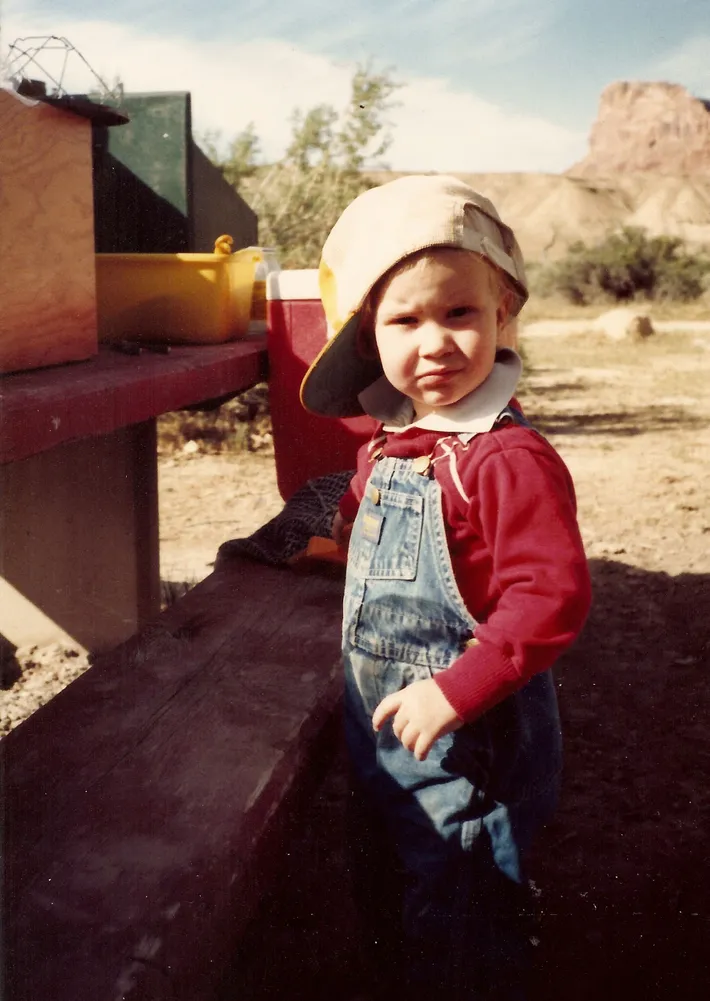

This photograph of me when I was 3 years old was taken at a camp and tells something about my parents. They believed that taking my brother and me outdoors and instilling curiosity for nature was essential to our development, so they started that process very early. This curiosity has helped me throughout my life.

Cory Richards, at approximately 3 years old in this photo, is grateful that his parents encouraged his curiosity for nature and encouraged him to be active.

During my adolescence, I felt like a social misfit. The truth is, I’m a very awkward and insecure person. I always felt like I was constantly changing, that I couldn’t fit in anywhere. So, I found my identity in the mountains because they didn’t demand me to be something more; I could simply be myself. In the mountains, I also quickly discovered that most rules are arbitrary. That what seems impossible, when taken step by step, isn’t. That if you break the process down, you can achieve almost anything.

I started high school two years earlier than usual, which was both beneficial and detrimental. When you’re 12 years old and hanging out with 18-year-olds, you’re in a very seductive sphere that can lead you astray. When I was 13, I stopped going to class and started using drugs. My parents were mortified as they watched my life unravel, so they admitted me to a behavioral treatment center, a place they thought would keep me safe.

But that place was terrible. I was there for 8 months, and in the end, what I learned wasn’t that I was a valuable young member of society, but that I was broken inside and needed fixing. Because of that lesson, I escaped from rehabilitation three times. Due to that toxic idea I had learned, and that I still carry with me, that somehow I was damaged and would always be. I’m still fighting against it.

One can imagine how my actions affected my family. In the end, my parents had to make the decision to let me go. Either they allowed me everything, or they let me go, and the first option would have destroyed my whole family. So, they made the best decision for themselves, and I don’t blame them, but it led me to live as a homeless person for a while.

All the time I spent on the streets was essential for my development because it gave me a perspective on what humanity comes down to. It provided me with the ability to feel empathy for those less fortunate. It also allowed me to see the reality of the human condition: what we are capable of, in acts of aggression and kindness, and more importantly, all that we can overcome. That idea extends to everything I do.

It took many years – during which my parents, friends, and family came back into my life – but eventually, I returned to the mountains, the only place where I felt safe and had an identity. Climbing is a wonderful allegory of human effort. I don’t think it was a coincidence that climbing, exploration, and adventure finally pulled me out of that tough stage.

The more I climbed and the more successful I became – as I turned into a professional climber and made money from it – I could also travel more. The more I traveled, the more disillusioned I became with what I was doing. It wasn’t that I didn’t love climbing, but there were stories around me that were much more important and needed to be told. I began to feel blind to climbing, as if I were being selfish. How could I, from privileged origins, employ those privileges to simply climb a mountain and celebrate myself, without celebrating everything around me? The human stories I found were incredible, and I wanted to tell them.

In the winter of 2010 and 2011, I was asked to go to northwest Pakistan to climb Gasherbrum II, an 8,000-meter peak on the border with India. The invitation came from veteran climbers: Simone Moro, an Italian, and Dennis Urubko, from Kazakhstan. I remember that when we reached 7,620 meters, I already knew we were going to reach the summit that day and that it would change my life. What I didn’t know was what would happen next.

When we climbed as a team, I became the first American to reach the summit of an 8,000-meter peak in winter. Afterward, on the descent, the weather began to deteriorate significantly. It was snowing more and more, and I heard a breaking sound behind me, and then something that sounded like a freight train. I shouted “avalanche!” but you can imagine what it’s like trying to run through thigh-deep snow.

We got hit, and I felt like I entered a much darker world than I could have ever imagined as I tumbled around and felt the weight of my body pulling me down. When I stopped, luckily, my face wasn’t covered in snow. I immediately thought, “Well, Simone and Denis are dead, and I’m going to have to get down the mountain by myself.” But then I suddenly heard Simone’s high-pitched Italian voice: “Cory, are you okay?” And I said, “Dude, of course I’m not okay.” I felt his hands as he dug to free me, and as soon as I was uncovered enough to move, I pulled out my camera. I turned it toward my face and took what is probably my most well-known photograph: my ice-covered grimace.

It looks like in that moment, I’m 90 years old. It’s horrible. My mom couldn’t even recognize me in that photo! But I want to highlight something very serious here: what I see on that face is severe trauma. I see a life about to shatter.

The three of us were on the brink of death. When your brain prepares for death the way mine did, something funny happens: it gets stuck in the experience. And if you don’t find a way out, that conflict becomes what we call post-traumatic stress disorder. I descended from Gash II that day without knowing the severe and deep affliction it would cause me for a lifetime.

I came back home and got married. We had incredible friends. But immediately after coming back from this adventure, I started feeling disconnection, that feeling like I was somehow looking at my life from the outside. I felt an incredible weight on me, pushing me down. I couldn’t remember some things. It was a kind of loud silence, a monotony with sharp edges.

And worse, this became my life: being on stage in front of everyone and telling the story, showing the photographs, and watching my film of me crying after the avalanche, over and over again. It’s something that traumatizes you again, but at the same time, I didn’t realize what was happening.

However, Gash II not only gave me a disorder. It also allowed me to enter National Geographic. By chance, when we were climbing, we found a Pakistani military camp right next to our base camp. I started taking pictures of these young soldiers. We had Internet, and these men wanted to watch movies, so they would often come to our camp for tea. They also asked if they could use my Facebook, and I let them. Now I have hundreds of friends named Mohammed, Farouk, and Ahmed, and that’s why I’m on the Transportation Security Administration‘s list… but it’s okay, these things happen.

The real beauty of all this was the access to their lives they gave me. It was an exercise in intimacy that taught me how to get close to people. And those were the photos that opened the doors to National Geographic editors, images that have an impact, that tell broader stories that need attention. Making that kind of photography has become my driving force.

During an expedition that Richards joined to photograph for National Geographic, a scientist climbs a rock wall to reach the 800-year-old caves of Mustang, Nepal.

My first assignment for the magazine was to go to the border between Nepal and Tibet, to an area called Mustang. We climbed to reach a complex of caves, hundreds of which had been carved into cliffs about 45 meters above the valley floor. Accessing them could be treacherous; once, while trying to climb up to one of them, one of the handholds broke, and I fell about 6 meters, injuring my back.

We wanted to go into these cave systems to uncover their mysteries. We were looking for burial crypts because that’s where we would find human remains, where we could find teeth. And teeth contain strontium, an element found in dental enamel that shows where on the planet you were born, based on what you and your ancestors ate and drank. So, if you find a tooth in one part of the world, but the strontium indicates that the person was born elsewhere, you can start to establish a valuable pattern of human migrations and trade.

For Richards, this photo of a polar bear on Rudolph Island epitomizes the effects of climate change in the Russian Arctic.

Why is this so important? Why do we need to study our past? To begin to understand where we thrived and where we went wrong. We are an exploitative species, and if we exploit our resources too much, everything will start to crumble. When humans make mistakes, these are not just our own, but they have an impact on everything around us.

Another of my later assignments was to the Fritjof Nansen Archipelago in the Russian Arctic. It is important for us to understand a place like this because it is 99 percent pristine and provides us with a beautiful and pure reference baseline for studying climate change caused by human actions. It shows us the effects we have on the planet: if we had visited it 100 years ago, the views would have been endless white. Instead, we found a polar bear walking on one of the last snowy terrains. This photograph is one of the most heart-wrenching I’ve taken. If our home is disintegrating around us, we will soon be without a home, and these are the issues we need to start paying attention to.

Another assignment started in the highlands of Angola. The country had been devastated by a bloody 30-year civil war during which the ecosystem had been preserved, keeping people and wildlife away from certain areas. Our job was to descend the 1,930 kilometers of an unexplored river basin. It started as a six-week journey but ended up lasting four months. Conflict had kept the natural environment safe, but as soon as landmines are removed from the ground, people will start settling and exploiting it, extracting its resources. It is really important to understand who uses the water, where, and how, as everything is interconnected. Why is a river basin in Angola so important? Because in southern Africa, there is a large floodplain called the Okavango Delta. It floods annually and is the beating heart of that area: when the waters invade it, animal migrations come to it, and when it dries up, they leave.

Practically every liter of water that enters the delta comes from the highlands of Angola. But the country, looking for new ways to make money, wants to find as many sources as possible. So it’s not just a story about a river basin, but about countries coming together to find a common ground that is allegorical for all of us. We are not independent from each other, so we must make better collective decisions as a human family.

As I worked, I felt connected to everything. But when I got home, I felt disconnected. I would sit in silence and feel this pain overtaking me, its source unknown. I didn’t know it came from the trauma of my adolescence and the trauma of the avalanche. I felt myself slowly retreating into this deep sense of loneliness, and at one point, the darkness within me erupted and simply became a darkness that surrounded me. I tried to climb Everest in 2012 and failed due to a panic attack lower on the mountain. It was that trip that led to the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Like many people in this situation, I began drinking heavily. I would wake up in the morning and promise myself I could make it to “happy hour” without a drink, but by 3 in the afternoon, I was having a drink. The time of day kept shifting earlier. I didn’t worry because I wasn’t drunk in public, so no one would notice. But I kept drinking to escape from everything I felt. I didn’t want to acknowledge it, but I was starting to have a serious problem with alcohol.

At work, I didn’t do it as often because I felt completely fulfilled: I was awake, passionate, creative—everything healthy. But eventually, going to work wasn’t enough of an escape.

In 2014, I joined a team heading to Burma and Hkakabo Razi, a peak they said was the tallest in Southeast Asia. Climbing the granite and glaciers was the second obstacle; the first was reaching the summit after crossing 240 kilometers of dense jungle. During that walk, I had countless hours of sweat to reflect on what I was trying to avoid through alcohol and other addictions. My life entered a phase of deep relief.

I was afraid to return to the mountains, to climb, to disappoint everyone. All the insecurities I tried to avoid by going to the mountains came back. My teammates didn’t know it, but there were times when I could barely move. After 40 days through the jungle and 10 days of climbing, we finally saw the summit for the first time. But just 24 hours later, we faced brutal terrain and weather, so we turned back. We failed. I failed. And I don’t think the success or failure of the trip was my fault, but I knew that the weight of the pain I carried inside me was pulling me down.

When I look back and contemplate my life, I see many great failures that have ultimately turned into small successes. Other people didn’t see them because I wasn’t living honestly. Behind the facade of an extraordinary career, I was falling apart. People saw my feats on social media, but they had never seen me drunk in a hotel room alone after giving a talk. I was being dishonest with those around me, and the gap between my facade and reality was widening.

I knew I would have to return home to a marriage I had neglected and that was failing because I was a bad husband. I had cheated, frequently. I was deeply unfaithful, and then I lied about it. I tried to drown my shame in alcohol and then tried to drown that alcoholism in the affection of others. And I just made it worse.

In a month, I blew up my marriage, destroyed a relationship with my main climbing sponsor, and left the production company I had co-founded with two friends. I simply reduced my life to ashes. And I felt like the child I had once been again, the child who left the system and was homeless at the age of 13. I was alone in the darkness, searching for answers.

And then, providentially, the same lifeline that had been given to me in childhood came to me: I was asked to return to Everest.

Everything started to connect. In May 2016, I returned with a new climbing partner, Adrian Ballinger. We wanted to bring people with us to the Himalayas through social media. On Snapchat, the hashtag #EverestNoFilter showed Adrian and me goofing off half the time, but it provided us with a way to tell an authentic story. Think about it: people connect much more when we stop showing only the beautiful part and start sharing the real part too.

Before the pair headed to Tibet for their Everest climb in 2016, Richards photographed Adrian Ballinger acclimating at 5,900 meters above the Khumbu Valley on the Tibet border.

We wanted to reach the summit of Everest – 8,848 meters high – without supplemental oxygen. When Adrian found it difficult at around 8,600 meters, he decided to selflessly end his attempt and let me continue. It was his decision to turn around that allowed me to reach the summit last year. This year, my main goal is to help him reach the summit.

As a cherry on top of last year’s climb, Adrian and I had planned to film a Snapchat from the top of the world. Later, when I arrived – this is the view – I opened Snapchat, and my phone turned off. What a great ending, really. I ran as fast as I could to get back to camp.

When I was on the summit of Everest in 2016, Richards said, “I stayed there for a total of 3 minutes… and I also had a pretty funny thought: this is the closest I’m ever going to be to space.”

The lessons began to accumulate at that moment and in the months that followed. I thought Everest would be something like an act of catharsis, that it would break the darkness I was in, resolve the post-traumatic stress, and make my guilt disappear. I thought it would be a phoenix rising from the ashes. But what I discovered instead was that I had had to run to the highest point on the planet to escape my truth, and I could no longer keep hiding it. Allegorically, Everest is the point from which everything else flows, or at least that’s what I see here. It’s from there that I had to descend into everything I had to face.

Why publicly talk about my divorce, post-traumatic stress, alcoholism, and infidelity and mix the conversation with adventures and an African river? Where do I want to go? The answer is simple: everything is connected. Our personal problems are inseparable from our global problems. What do we do to address climate change and how do we contribute to it? What are the solutions to cultural corrosion? How do we approach conflict and care for those affected by it? Where are the voices for those who have no voice, and what would they tell us?

For me, everything has a single solution: honesty. Truth matters because it’s not just my story. It’s our story.